In December of last year, Vermilion Energy (VET) announced the acquisition of Westbrick, an oil and gas company operating in the Deep Basin portion of Alberta. The acquisition was for CAD 1.075 billion, and Westbrick had been producing approximately 50,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day. Vermilion believes that they can increase that production to 60,000 BOE/day, and still have fifteen years of reserves. The market reaction at the time was negative, the market only wants share buybacks while energy companies are at historically low multiples. But Vermilion is run by petroleum engineers, and they want to drill. VET does share buybacks, but only with “excess free cash flow,” the scraps from the table after the drilling programs are funded.

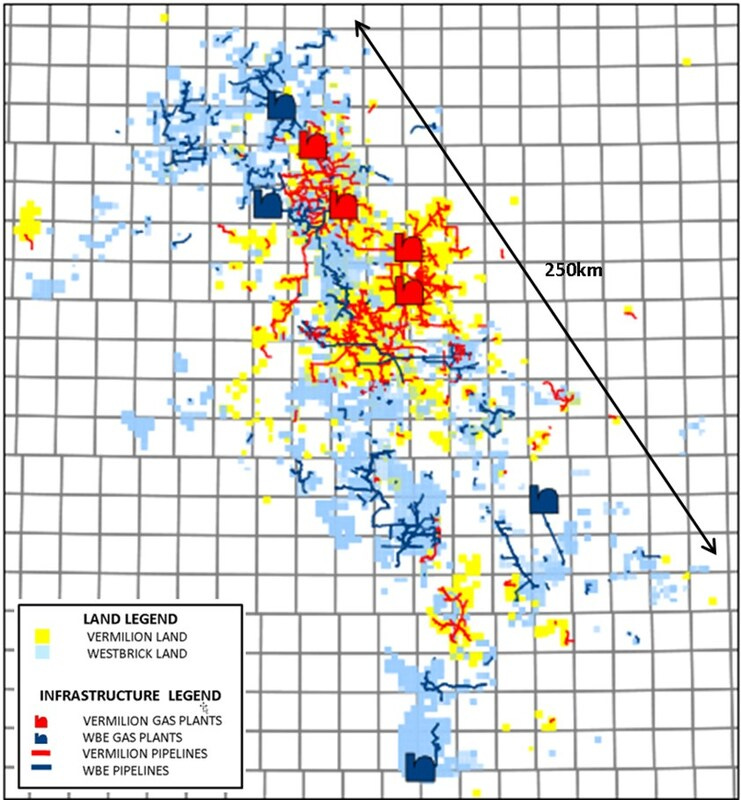

The acreage of Westbrick was contiguous with Vermilion’s largest producing asset, which means that there should be some cost savings and efficiency gains associated with the acquisition. For all my criticisms of VET management, while they don’t pride themselves on the share price, they probably will pride themselves on operational efficiency gains.

I did not originally underwrite my purchase of VET shares based on North America production, but the recent acquisition, as well as the artificial intelligence revolution, does change things. In order to reduce the debt burden, as well as to rationalize operations, Vermilion sold their assets in Wyoming and Saskatchewan. Those assets were 80% and 85% oil, respectively, meanwhile the Deep Basin asset is only 25% liquids, and those liquids are split between oil and NGLs, natural gas liquids (propane and butane). The Westbrick acquisition, and the Wyoming and Saskatchewan disposition, have left Vermilion as primarily a natural gas company, and they even updated their investor presentation accordingly.

“Internationally Diversified”:

“Global Gas Producer”:

I’m also happy that corporations are slowly dropping ESG from their priorities.

The Wyoming Asset produced about 5,500 BOE/day, had 5 years of reserves, and sold for CAD 120 million. The Saskatchewan asset produced about 10,500 BOE/day, had 7.8 years of reserves, and sold for CAD 415 million. Those proceeds will retire about half of the debt incurred to make the acquisition, which produces 50,000 BOE/day, with a target of bringing production to 60,000 BOE/day within the next five years. Even with the other assets around 85% liquids, and the Deep Basin around 25% liquids, the asset swap leaves liquids production mostly unchanged, albeit with a heavier tilt toward NGLs over light oil. Also, last quarter Wyoming only produced 4,000 BOE/day, not the stated 5,500, possibly due to maintenance downtime, or possibly that asset was in rapid decline.

Vermilion more than doubled the asset life for approximately CAD 500 million, leaving liquids production mostly unchanged, and they got enormous exposure to Canadian natural gas. Management is guiding for that asset to generate over $110 million of free cash flow per year, but that is after the heavy drilling program to increase production. Free cash flow from the acquisition should increase over the next few years when production gets into a steady state and drilling programs slow down. But those estimates do not include any potential upside from underlying commodity prices rising.

The natural gas produced in Canada sells at a benchmark called AECO (Alberta Energy Company), so that’s a new number to keep track of alongside Henry Hub and Dutch TTF. Since natural gas is difficult to ship and to store, AECO prices have remained very low, around CAD 1.50 to CAD 1.90 per mcf, or 1/6th of a barrel of oil equivalent. So while the oil produced can sell at over CAD 100 Brent, the natural gas sells for about CAD 9 to CAD 12 per barrel equivalent. The natural gas liquids are trading for around CAD 40 per barrel equivalent.

I’m not relying on Mark Carney to build new export pipelines, his party is the one responsible for preventing new pipelines for the last fifteen years. But as the US builds more export terminals, and as Artificial Intelligence consumes more electricity, there should be enough transport capacity on the margin to influence AECO prices, even if they stay far from parity. Vermilion’s production of North American natural gas is now so large, that every CAD 1.00 would be worth about CAD 165 million in annual free cash flow. The think tanks that make predictions on AECO seem to think that we’ll be at CAD 2.50 soon, and CAD 3.50 isn’t off the table within a few years.

When I first bought shares of Vermilion, I did it primarily for the European natural gas production. It was just after the start of the Ukraine War, and with trade embargoes against Russian imports, there was no telling how high the price of natural gas would go in Europe. The trade embargoes weren’t so ironclad, natural gas still flowed from Russia to Europe, in relatively high volumes until somebody (probably the US) blew up the Nordstream pipeline. On top of that, Europe had two back-to-back unseasonably warm winters. This was probably due to the Hunga Tonga volcano that erupted at the bottom of the ocean, sending enormous amounts of water vapor into the upper atmosphere. Unlike carbon dioxide, water vapor is a potent greenhouse gas. If the Hunga Tonga volcano really was responsible for warmer winters, the effects are anticipated by some scientists to last another five years.

I had also expected the Ukraine War to end, especially with Donald Trump trying to broker a peace deal. I still find it amazing that Lindsay Graham and Mike Pompeo flew to Ukraine in clear violation of the Logan Act, to encourage Zelensky to escalate the war and scuttling the peace negotiations. Natural gas prices might stay high in Europe for a while yet, maybe Iron Maiden was right and the war pigs really do have the power.

The European production is ongoing, and growing organically through new drilling programs. The margins are fat, and even if a peace deal were achieved to end the war, a belligerent Europe might maintain sanctions on Russia until well after Vladimir Putin succumbs to old age out of spite.

But now that Vermilion has a large, consolidated, slow-decline, natural gas asset which will soon be producing over 100,000 BOE/day, it might make a good acquisition target. As a small cap investor, one of the more common ways that I miss out on returns is if the company gets taken private or sold before the price can move too high. The argument against VET as a potential acquisition target was that their assets are too small and too scattered. But now Vermilion’s assets are considerably less scattered, and more natural gas focused. While ESG might be in a bit of a retreat, natural gas is looked upon much more favorably than oil. I would no longer be surprised if VET were acquired, given their low share price compared to operating cash flow.

In 2022, Vermilion produced 85,187 BOE/day, and they had 169 million shares outstanding. Today they have 154 million shares outstanding, and are guiding for between 117,000 and 122,000 BOE/day for 2025. In 2022, each share of VET was responsible for 8.83 gallons of annual hydrocarbon production, in 2025, that number will be over 13.31 gallons, and there are three quarters left for more share buybacks, which are slow, but not negligible. Production per share of VET has compounded at 14.65% during the last three years, and for two of those years energy prices were low. Also, VET paid $1.28 in dividends over those three years, increasing the quarterly payout from CAD 0.08 to 0.13, a 17.56% dividend growth rate.

In 2022, we were at the peak of a cycle in energy prices, and Vermilion had CAD 1.6 billion funds from operations, CAD 1.1 billion in free cash flow. And that was on 85,000 BOE/day. How much will they earn at the peak of the next cycle? Energy is cyclical, and I don’t know if the next cycle peak will be in a year or three, but it will come again. When it does, Vermilion traded at a multiple of about triple where it is today. The stock price feels like it’s been doing nothing but falling for three years, but the fundamentals have been compounded at double digit rates.

The chart looks like the stock finally found the bottom of the barrel, and is ready to make its slow climb back to over $20 a share after three years of crashing. I do wish that management had gone a little heavier with share buybacks during this time period, but aside from that complaint, they have been doing what CEOs of all cyclical commodity producing companies say they should do, looking past the cycle. Vermilion embraced producing hydrocarbons in Europe when most other companies were divesting. Sure, they were hit with a windfall profits tax, but they still had a record year of profitability. Now Vermilion is embracing Canadian natural gas at a time of peak pessimism for Canadian energy companies after Mark Carney’s electoral victory, but I suspect that over time, competition will narrow that gap between Henry Hub and AECO just a bit. And every CAD 1.00 that AECO rises, VET makes another CAD 165 million of free cash flow.

You can find my original writeup on VET here:

When the stocks you love don’t love you back, Vermillion Energy $VET edition.

Hey ChatGPT, please dunk on Vermillion Energy in the style of Shakespeare’s Sonnets 88-90.