Staples Thunderdome: B&G Foods $BGS vs Seneca Foods $SENEA

Two Stocks Enter, One Stock Leaves - Welcome to Bartertown

I don’t go digging through consumer staples often; similar to utilities and REITs, I find the whole sector a bit of a snoozefest. But when I see insider buying and a stock price that has crashed through the floor, I give it a decent look.

B&G Foods (BGS) is a brand conglomerate with an aggressive acquisition history that is feeling their debt burden. They have a lot of brands, but how much Clabber Girl baking powder is sold every quarter? And how many of their products have cheaper substitutions on the shelves? This group of products might not have the best position for the K-shaped economy theme.

Only about 5% of c-suite executives ever engage in insider buying, it takes a lot to jostle them out of the mentality of being an employee. Seeing a stock price that should triple is one of the things that can do it. But while executives have a good idea if the stock is cheap, they typically have a terrible idea on the timing for when the stock price will recover. You can see here that the insider buying started in earnest when the stock price was about 30% higher than it is currently. Thinking about separating the noise from the signal, CEOs tend to be optimistic by nature, but an insider buy from the Chief Financial Officer and the General Counsel carry a lot of weight with me. BGS doesn’t have a COO, that role is split between four division heads, one of whom also bought in.

The insider selling also gives some idea of a medium term upper limit to the opportunity. Insiders were selling at about 2.5x the current share price. The peak market capitalization was in 2016, and that was about 6x higher. The peak price to sales ratio or price to book ratio was at a share price about 4x to 5x higher than today’s stock price. But the momentum is terrible. This knife might not be done falling,

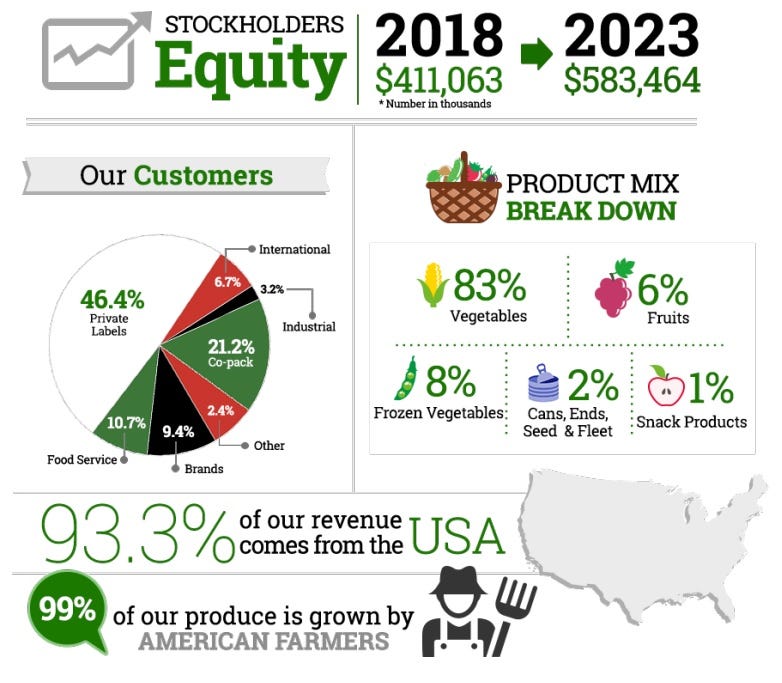

Seneca Foods (SENEA) is a vegetable cannery with about half of their revenues coming from white labeling. An interesting potential growth vector is the expansion out of canned vegetables and into packaged snack foods.

Seneca has fewer brands of their own, but as a white labeler, they are their own competition, and this has provided them with a better place to weather the K-shaped economy. SENEA is already trading at their peak historical price to sales ratio, and their price to book ratio only implies about a 20% upside from here, but the market treats packaged snacks very differently from canned vegetables.

Seneca is also not without their own insider buys, and also from the CFO, which I value very highly, but at prices 30% lower than the current share price:

The momentum has only been up since June of 2023, and Seneca bought the rights to Green Giant (canned but not frozen) from BGS.

The performance has been so strong, there have even been a few memes that caught my eye over the last year.

I believe that part of the allure of Seneca to some retail investors has been their inventory, due to the seasonality of vegetable harvests, the canners maintain an enormous working capital in their warehouses. A mantra on twitter has been that the market capitalization of $480 million is half of the $950 million of canned goods that the company owns. But this isn’t a great inflation strategy, as SENEA will have to keep adding to their working capital as costs rise. It does have a certain attraction for people who romanticize doomsday prepping though.

One of the things I find fascinating about this head to head comparison is that the companies have very similar market capitalizations $496 million for BGS vs $482 million for SENEA , and reasonably similar trailing twelve month sales, $1.96 billion for BGS vs $1.48 billion for SENEA, but one is bombed out and the other is at new highs. The bombed out BGS is trading at a price to sales ratio of 0.25x, but the new all time highs SENEA is at 0.33x. But in 2016, BGS was trading at a price to sales ratio of 1.32x while SENEA was trading at 0.28x.

There are two things that drive up multiples, quality and growth. The growth is somewhat similar, both have approximately doubled revenue per share over the last twelve years. So that huge multiple for BGS must have been for quality, at one time BGS was a stable brand conglomerate, somewhat comparable to Campbell’s Soup (CPB), which trades at a price to sales ratio of 1.35x today. Can BGS convince the marketplace that it is quality again? It’s hard to prove that your earnings are stable after they haven’t been stable. But can Seneca convince the marketplace that it has become quality for the first time? Maybe.

BGS Net Income:

When you look at BGS’ net income, there are three quarters of huge write-offs, capital impairments, and capital losses on the sale of Green Giant shelf stable. But under the surface, they have had positive operational cashflow despite generating GAAP losses for the last two years. Are the write-offs and impairments over with and can BGS go back to generating stable profits? Maybe.

SENEA Net Income:

When you look at Seneca’s net income, you see a company which in the past had very unstable incomes, but by about 2020, transformed into a company with very stable quarterly profits, (aside from a one off cost in 2023). So even though SENEA has never traded above a price to sales ratio of 0.33x for its public existence, there are decent odds that it could going forward due to the change in quality.

Seneca is also considerably less indebted than BGS. SENEA has about $442 million of long term debt, and it has been paid down aggressively from the peak of $624 million after the Green Giant acquisition. BGS has about $1.8 billion in long term debt, down from about $2.4 billion after the Crisco acquisition. SENEA has a looming debt maturity in June of 2025, but it is only $100 million. BGS has no maturities until 2027, but they come fast and furious with $550 million in 2027, and $1.1 billion due in 2028. With trailing twelve month EBITDA of $305 million compared to interest expense of $158 million, BGS is in some moderate trouble. Management is discussing more asset sales to try and dig themselves out of this hole. If those asset sales cause capital losses or impairments, then the GAAP net income may take more hits in the near future.

BGS is still maintaining their dividend which is costing the company about $60 million a year. They must be really confident in their ability to refinance debt at tolerable interest rates, and I hope they are not mistaken.

BGS also has some potential risk from Robert F Kennedy Jr targeting seed oils, that Crisco acquisition is an important part of BGS’ business. Alternatively, if RFK Jr makes tallow great again, maybe we’ll see Crisco branded beef tallow in our local grocery stores soon.

On a positive note, Seneca has room to grow into the packaged snacks space with their apple chips. But BGS has been experiencing growth in their spices category. As the top part of the K-shaped economy becomes wealthier, they spend a lot more snazzing up their food with various rubs and spice blends. McCormick’s (MKC) just announced an earnings beat and a raise to their dividend. In a few quarters, BGS could regain some multiple expansion as it tries to claw its way back as a quality name, but also as a growth story in spices.

Conclusions:

Seneca has a very real chance to double in the medium term despite trading at all time high valuations. It isn’t exactly a value degen pick, however, it’s a pick based on the transformation of low quality stock into a higher quality stock. I’m not buying here, but if the market had an overall correction in 2025, and I had any dry powder to deploy at a lower price, I could be tempted.

BGS is precisely a value degen pick, but I am often early. While the stock seems incredibly cheap, on another goodwill writedown or asset impairment, it could easily get cut in half again. Alternatively, Q4 is seasonally their strongest quarter due to holiday recipes, when else does the average shopper buy Grandma’s Molasses? An earnings beat next quarter could start the fundamental inflection that gives the stock a bounce. Given that we are in a consumer armageddon and a K-shaped economy with the greatest pain hitting the middle class, I think the odds are more in favor of an earnings miss and a continued price decline. But this is one stock that I am keeping on my watchlist for the right moment to buy.

In the meanwhile, I will be adding to my Newell Brands (NWL) position, as their turnaround story had a significant head start, but the stock price only responded on the fifth quarter of sequential improvement. If that pattern holds for BGS, there is no hurry to buy yet. With any luck, I will be able to take some profits from NWL in the future and rotate them into BGS before the price starts to run.

Why Newell Brands' $NWL turnaround strategy is fundamentally sound.

Capital markets are a second career for me, and after ten years of paying my dues in my first career, I knew that I didn’t have it in me to do things the hard way again. I have become obsessed with trying to find those pieces of information which are the signal through the noise and can dominate a large number of other concerns.

Update 11/21/2024:

Thank you to Harris Perlman for sharing this writeup with his 20,000 twitter followers. I really appreciate it, and I appreciate the constructive criticism. I was using Seneca mostly as a contrast to better compare B&G, but Seneca is worth a closer look on its own.

Just as was the case in my writeup on the St. Joe Company (JOE), for Seneca, the book value understates the inventory. For JOE this was due to the acquisition of land decades in the past, and book value being maintained at cost. For Seneca this is due to LIFO, last-in-first-out accounting. Keep in mind, for Seneca’s physical inventory of canned foods, the cans themselves are moved in a FIFO system, first-in-first-out, otherwise, there would be ancient and decomposing cans in the back of the warehouses. But in the accounting framework, the nominal cost of those first canned vegetables are still the cost basis of much newer canned peas and string beans.

Inventory hit a recent minimum of $343 million in 2021, which means that everything beyond that number is kept at a more recent cost basis, but everything below that number has a cost basis from before 2009, the last time that level of inventory was reached. That equates to about a minimum of a $170 million stealth value of their inventory. SENEA’s $950 million of inventory held on book value, is at least $1.12 billion of inventory in real terms, and likely somewhat more than that.

Why would the company do this? It lowers the annual tax bill by a bit because it understates profits. If every year, the older cost inventory were sold, there would be an inflation benefit. That inflation benefit still accrues, just not in a way that is easily seen in net income, you would have to follow the annual change in cash instead. The drawback is that if that old inventory were ever liquidated, there would be a long term capital gain, but this is unlikely as long as SENEA is a going concern, there is a certain amount of inventory they will need to maintain to keep smooth operations.

So SENEA’s true annual net income is closer to $100 million than to $40 million, putting it at a price to earnings ratio of about 4.5x. There are plenty of old economy businesses you can buy at a PE of 4.5x in steel mills and energy, but that is a very attractive price for consumer staples. It doesn’t really change my original conclusion much, however, as SENEA is currently trading at its highest price to sales ratio ever, and I do believe it can increase from here as the stability (quality) of earnings has improved. But I still wouldn’t sell my Newell Brands to buy Seneca unless it suffered from some sort of a dip. My best guess it is a medium term 2x, if the market comes to appreciate its quality, and there is no guarantee of that.

Thanks again to Harris Perlman who rightfully noticed that I gave his baby short shrift. Seneca is still a decent value, it just isn’t a degenerate value. I wish I had read Harris’ analysis back in August before the recent price runup. At the current valuation, both of Seneca and the market overall, the chance of a near term pullback is too high for my fancy.